Aug 27, 2013

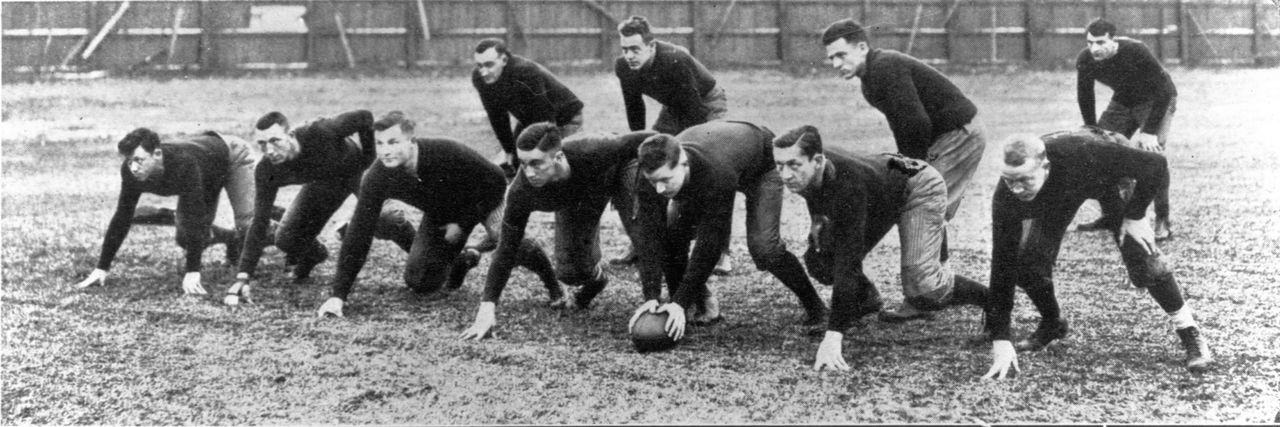

Football at Notre Dame officially began Nov. 23, 1887, when the University of Michigan team traveled to the South Bend campus to introduce the rules and intricacies of the game that was still in its infancy.

With an eight-year football history under its collective belt, Michigan scored two touchdowns (worth four points back then, and not six until 1912) and recorded an 8-0 victory, with no second half played.

Nevertheless, some popular opinion holds that the true “birth” of Notre Dame’s football program didn’t occur until Nov. 1, 1913, the day it upset powerful Army 35-13 in West Point.

That day was a confluence of many factors — innovation, national scheduling, powerful leadership at the top, a can-do spirit and legendary players — that would make Notre Dame’s football program maybe the most famous and successful brand name in intercollegiate athletics over the next 100 years.

Setting The Table

The 25 years from 1887-1912 had two main on-field landmark events for the Notre Dame football program.

One was halfback Louis “Red” Salmon in 1903 becoming the first Notre Dame player named to Walter Camp’s All-America unit (third team).

Next was the 11-3 upset of head coach Fielding Yost’s Michigan team in 1909 after having gone 0-8 all-time against the Wolverines. However, that only precipitated a fall-out when hours prior to the 1910 Notre Dame-Michigan meeting, Yost cancelled the contest.

The small, Catholic school with a limited identity in the Midwest had been ostracized by the Western Conference (now the Big Ten) during its fledgling years, and it had no full-time head coach or athletics administrator to lead it out from the wilderness (it had 10 different head coaches from 1899-1912, none going beyond two years).

While its football spirit was willing, Notre Dame’s frustration was manifested with its schedules.

The eight-game 1911 slate featured unglamorous home games against Ohio Northern, St. Viator, Butler, Loyola (Chicago) and St. Bonaventure teams that Notre Dame outscored 216-6.

The following season, the schedule was even less appealing with the addition of local schools such as Adrian and Morris Harvey. The lack of significant marquee value to such contests left the Notre Dame athletic budget in the red financially and at a crossroads. Either a full commitment had to be made toward the football program, or it would have to be eliminated, which had become unacceptable.

Notre Dame president Rev. John W. Cavanaugh opted for the former and hired 29-year-old Wabash head coach Jesse Clair Harper as the school’s first athletics director (the athletic department had previously been operated by student managers) and first full-time coach in football and baseball. Harper had played for and was a disciple of Amos Alonzo Stagg, who had developed a reputation as college football’s grand master in innovation while coaching at the University of Chicago.

A young, hungry coach on the rise and an ambitious, rising program ready to commit to the big time can be a potent combination. That marriage between Harper and Notre Dame soon changed the landscape of college football.

Notre Dame Takes Its Show On The Road

Although Notre Dame was a Catholic institution, Harper’s blueprint to make Notre Dame relevant in football was to operate on a famous Islamic tenet: “If the mountain will not come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the mountain.”

Translated to Notre Dame’s situation, it meant that if the football team was going to be blackballed from playing against the big-name Midwestern schools, then it would have to carve its own path the harder way by traveling across the country to make its “brand” known. The football players might have to be proverbial sacrificial lambs while traveling greater distances against supposedly superior foes, but it would be done so with larger guaranteed gate receipts to build up the athletic department’s financial coffers in years to come.

It was somewhat akin to advancing Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) teams of today such as Troy, Florida Atlantic or Western Kentucky, etc. — taking on an SEC power or others on their home turf in order to get a huge payday. Although the indefatigable Harper endured his share of expected rejection, he also achieved some major coups while contacting schools across the country for possible games.

The most notable came from West Point which happened to have its 20-year series with superpower Yale cancelled at the end of the 1912 season. The Army Black Knights need a replacement game, and Harper was able to haggle an initially reluctant Army brass into receiving a $1,000 payment to travel to the game.

Six days after covering about 875 miles and 24 hours by railroad for the Nov. 1 meeting with the Black Knights, Notre Dame had to travel 520 railroad miles to State College, Pa., to play Penn State, which had finished unbeaten (16-0-1) the two previous seasons.

There would be no rest for the weary that month at Notre Dame. Another arduous back-to-back road trip would ensue later that month when the “Catholics” traveled 400 miles to St. Louis to play Christian Brothers, and then rode the rails on another 840-mile trek to play the Texas Longhorns, who were sporting a 12-game winning streak, on Thanksgiving Day (Nov. 27).

And It Came To Pass

It was one thing to concoct a schedule that would see Notre Dame play all four of its games in November 1913 on the road while covering more than 5,200 miles during that span. (Prior to the 1913 season, Notre Dame’s longest previous road trip had been 415 miles to Pittsburgh.)

It was quite another to emerge victorious in all four.

After starting the 1913 season 3-0, including a 20-7 victory at home against first-time opponent South Dakota, Notre Dame embarked on its greatest program-changing month in its football annals, first by stunning unbeaten Army (its lone defeat over a span of 20 games), 35-13, and then avoiding any letdowns while also vanquishing Penn State (14-7), Christian Brothers (20-7) and Texas (30-7).

The highlight, though, was the monumental upset of Army, spearheaded by the passing tandem of quarterback Gus Dorais and end Knute Rockne, who had starred on the track team. The pass had been legal in NCAA football since 1906, but eschewed by most everyone because it appeared to be too much of a gimmick and was the antithesis of the ruggedness required in the game.

For Harper, though, status quo was not the way Notre Dame was going to separate itself from the hundreds of schools playing football. It was already going outside a comfort zone by scheduling nationally. The next step was to distinguish itself by its play on the field.

Notre Dame jolted Army early with a 25-yard touchdown pass from Dorais to Rockne for a 7-0 lead, but the aerial attack was barely used the remainder of the half, which saw the Catholics cling to a 14-13 edge. In the second half, Harper had Dorais winging the football with regularity, and his timing and accuracy left Army befuddled, thereby also opening up huge holes for fullback Ray Eichenlaub, who scored twice on running plays, and Joe Pliska catching a five-yard scoring toss from Dorais.

Reports vary, but it is generally agreed that the 5-7, 145-pound Dorais completed 14 of 17 passes for 243 yards with two touchdowns, ungodly numbers back then.

Wrote the New York Times: “The yellow leather egg was in the air half the time, with the Notre Dame team spread out in all directions over the field waiting for it. The Army players were hopelessly confused and chagrined before Notre Dame’s great playing, and [Army’s] style of old-fashioned, close line-smashing was no match for the spectacular and highly perfected attack of the Indiana collegians.”

Notre Dame’s receivers caught their passes on the run while Dorais “tossed the football on a straight line for 30 yards time and time again,” according to The Times.

During the turn of the millennium in 2000, ESPN featured a countdown of the “Greatest Coaching Decisions of the 20th Century.” Harper’s strategy of using the forward pass at Army in 1913 ranked No. 6 in any sport — and No. 1 in college football.

Epilogue

The amazing 7-0 campaign in Harper’s debut also saw the football team achieve another milestone when for the first time it netted a profit — $1,364 — at the conclusion of the 1913-14 academic year.

Until 1913, only two All-Americans had been recognized at Notre Dame. After the 1913 season, Dorais, Rockne and Eichenlaub eclipsed that figure by more than 100 percent.

The football team’s nickname “Catholics” would eventually change to “The Ramblers” during the Rockne era (1918-30) because of the many travels across the country. But the tradition originated in 1913 under Harper, who the following season would make the graduated Rockne his right-hand man as an assistant.

In fact, almost all that has made Notre Dame Football one of the United States’ most popular brands in 2013 can be traced back 100 years ago to the events of 1913.

— Lou Somogyi, Blue & Gold Illustrated