Sept. 2, 2015

Debates will eternally linger or rage about who is the greatest and most famous football player ever to don the Notre Dame uniform.

Johnny Lujack, the 1947 Heisman Trophy winner and college football’s lone three-time national champion at quarterback, is often a popular choice to historians because of his prowess on both sides of the ball.

Consummate triple threats — offense, defense, kicking game — Johnny Lattner and Paul Hornung, the 1953 and 1956 Heisman recipients, also merit legitimate consideration. An argument today can be made that no Notre Dame football player has more recognizable name value than Joe Montana, even though his NFL career was more hallowed than when he guided the Fighting Irish to the 1977 national title.

This year, Tim Brown became the sixth Notre Dame player ever to be enshrined in the College and Pro Football Halls of Fame, joining Wayne Millner, George Connor, Hornung, Alan Page and Dave Casper — although many would contend that Brown’s successor, Raghib “Rocket” Ismail, from 1988-90 was an even better game-breaker than Brown as a runner, receiver and return man.

Defensively, end Ross Browner was a linchpin on the 1973 and 1977 national title teams during which time he recorded 77 tackles for loss (no other Notre Dame player has more than 44.5).

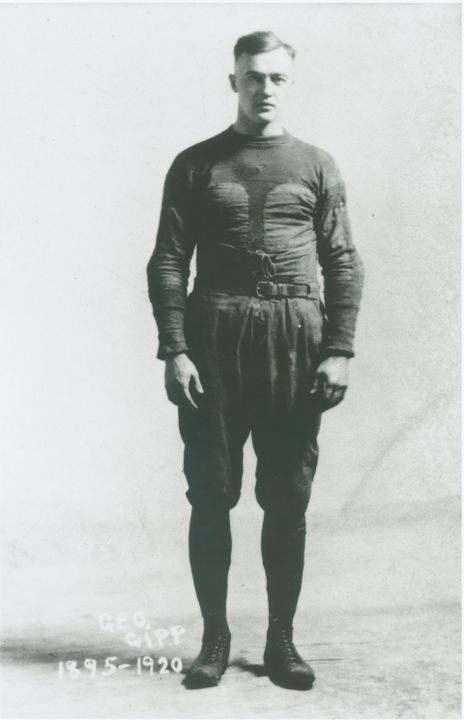

Yet no single Notre Dame player has, and maybe ever will, passed the test of time the way 1916-20 halfback George Gipp has. One hundred years from now, “The Gipper” still will remain an indelible part of college football lore and Americana.

Gipp, a consensus All-American at Notre Dame, led Knute Rockne’s squads to consecutive unbeaten seasons (19 straight wins) as a junior and senior in 1919-20. His 8.10 yards per carry as a senior remains the school standard. During the two unbeaten years with Rockne, he rushed for 1,556 yards (averaging 7.5 yards per carry), averaged an extraordinary 10.7 yards per his 134 pass attempts, intercepted six passes, averaged 40 yards on 40 punts and kicked 20 PATs.

His premature death at age 25 and the request to some day “win one for the Gipper” only helped magnify the legend and the life immensely. It didn’t hurt to have future president Ronald Reagan (1981-89) portray his character in the 1940 film, “Knute Rockne: All American.”

TRAGIC HERO

This year marks the 95th anniversary of Gipp’s death and 120th anniversary of his birth on Feb. 18, 1895 in Laurium, Mich., one of eight children born to Matthew and Isabella Gipp.

Part of the legend and lore of Gipp is he was the antithesis of the classic Notre Dame student-athlete that is so well publicized today. Gipp was perceived as a wayward soul, yet one embraced by the school despite not seeming like the ideal fit. Like marriage partners who seemed opposite of each other, they made it work to their advantage rather than let it dissolve.

Starting from his grade school days, Gipp’s academic record was deemed poor, mainly because he was bereft of motivation to excel in that area of his life. Consequently, in his early years he didn’t even compete much in sports because he wasn’t in school long enough.

As a teenager, he transferred to a junior high school in Calumet, where much of his time was spent at the YMCA. It was there he was introduced to athletics, and he played the big three seasonal sports — football, basketball and baseball — where he displayed a natural aptitude. Yet the one where he especially displayed a marvelous proficiency was in the individual sport of billiards. Unfortunately, he lost much school time because of his newfound love of competing in athletic endeavors, which also reaped financial benefits.

School records disclosed that Gipp never finished Calumet High School, and soon thereafter Gipp was employed with a construction company, drove a taxi for three years and waited on tables at the Michigan House Restaurant. It was there Gipp met Angelo Pappas, who would become his closest friend and help him financially in the future at Notre Dame.

In addition to his various means of employment, Gipp played center field for the Laurium town baseball team with such prowess that both the Chicago Cubs and Chicago White Sox reportedly made overtures to sign Gipp. Word of his talent spread to Notre Dame, where he received an offer to attend school on a baseball scholarship.

At age 21, Gipp enrolled as a college freshman — just like his future head coach Knute Rockne did in 1910 after working several years in the Chicago post office — and his waiter skills were used on campus for the first semester to pay for room and board while he lived in Brownson Hall.

After that term, he moved into the downtown Oliver Hotel, where his rent was paid for with his skills with his cue stick and talent at the card tables. According to esteemed Notre Dame historian Thomas Schlereth in his “The University of Notre Dame” book, Gipp was the “pocket and three-cushion billiards champion of South Bend, womanizer, laconic, aloof, troubled young man who became a tragic hero.”

Such is how legends are often forged.

THE FOOTBALL PATH

As head coach Jesse Harper’s assistant from 1914-18, Rockne’s discovery of the freshman Gipp occurred when he observed him drop kicking with ease a football, in street shoes, well over 50 and 60 yards.

Invited to try out for the team, Gipp’s first three seasons were relatively uneventful, and there almost wasn’t a fourth and fifth.

He played primarily for the freshman team in 1916, and then in 1917, Gipp didn’t even arrive on campus until the first two football games had already been played. After playing in the next three games, highlighted by rushing for 110 yards in a victory over South Dakota, Gipp suffered a broken leg on the first play from scrimmage when he ran for 35 yards.

His junior campaign in 1918 — Rockne’s first as the new head coach — was decimated by two factors. One was a couple dozen players at Notre Dame had departed overseas during World War I. Gipp also tried to enlist but was turned down. Second was a worldwide influenza epidemic that affected 500 million people and led to the cancellation of all football games in October. Thus, the NCAA declared that 1918 would not count against a player’s four-year eligibility.

In May 1919, after the war was over, Gipp was expelled from Notre Dame for missing his final exams (maybe not coincidentally, on May 3 of that year he became recognized as the top pool player in the state). He apparently was readmitted when an oral examination to compensate for his missed classes proved sufficient. It made him available to begin the groundwork of Rockne’s crew becoming America’s Team in the 1920s.

From the left halfback slot, Gipp was the team’s top passer and runner during both of those campaigns while spearheading back-to-back 9-0 campaigns. Highlighting those seasons were hard fought 14-9 and 16-7 wins over previous nemesis Nebraska, plus 12-9 and 27-17 conquests of what had become arch rival Army. For the first time, Notre Dame was recognized as the Champions of the West, although eastern football, especially with the Ivy League programs plus Army, was still classified as supreme. Rockne’s team even received some national title recognition both seasons by different systems of voting.

In 1919, his 729 yards rushing averaged 6.9 yards per carry, and his 727 yards were completed at what back then was an extraordinary .569 completion rate while averaging 10 yards per attempt.

Then in his final season in 1920, Gipp became the first player from Notre Dame to be named a Walter Camp All-America. The campaign was highlighted by an extraordinary effort at Army in which he rallied the troops from a halftime deficit to victory while carry 20 times for 150 yards and completing five of his nine passes for 123 yards, plus starring on defense and as a punter.

Again, enhancing the Gipp legend was his nonchalance. When Rockne ripped into him at halftime of the Army game for not caring enough, Gipp informed him that he had bet too much on the game in Notre Dame’s favor to let the game be lost.

According to Norm Barry, who played four seasons with Gipp, no other player could have done to the taskmaster Rockne what he did.

“Everybody thought that Gipp was greater than Rockne,” Barry said. “He was the big man and he deserved to be. He carried the ball most of the time … Whenever he was in a critical situation, he always knew how to handle it.”

The fact that the ultra-talented Gipp would come to practice based on his own time schedule — and if wanted to — would rankle Rockne, yet never enough to dismiss him. He was wise enough to know who buttered his bread. “Gipp was in Mishawaka playing poker one time and got over late for practice, ” recalled another former teammate, Paul Castner. “As he came on the field, Rockne, out of the corner of his eye, saw him and said, `Gipp, if you can’t get here on time, go back and take your uniform off!’

“And Gipp did just that. He took off his uniform and went back to the poker game.”

Through the first seven games in 1920, Gipp rushed for 827 yards at 8.1078 yards per carry, a single season standard that still remains for the Fighting Irish. But while leading Notre Dame to a 13-10 victory versus Indiana after trailing 10-0, an injury sidelined him against Northwestern, where a then extraordinary crowd of 20,000 chanted for his insertion into the game. When he made a fourth quarter appearance, Gipp did not but run but completed five of his six passes for 157 yards and two scores in the 33-13 victory.

By the Nov. 25 finale at Michigan State (a 25-0 victory), Gipp was already laying in St. Joseph’s Hospital, where he would pass away on Dec. 20 from pneumonia and a strep throat.

INTO IMMORTALITY

In death, the Gipp legend grew even more when he supposedly made the following entreaty to Rockne: “I’ve got to go, Rock.

It’s all right. I’m not afraid. Sometime, Rock, when the team is up against it, when things are wrong and the breaks are beating the boys, ask them to go in there with all they’ve got and win just one for the Gipper. I don’t know where I’ll be then, Rock. But I’ll know about it, and I’ll be happy.”

Eight years later at Yankee Stadium on Nov. 10, 1928, Rockne relayed that story to his struggling Fighting Irish, who then rallied to defeat unbeaten Army, 12-6, in front of a capacity audience of 78,188.

Wrote Notre Dame football historian Bud Maloney on the 100th anniversary of Gipp’s birth in 1995: “One modern author after another has asked whether Gipp’s request was ever made. They mediate on the personalities of the both Gipp and Rockne, study the hospital circumstances, try to interpret what little is factually known — then have to conclude that we’ll never really know.”

What always will remain known is in Notre Dame football lore, Gipp will remain unsurpassed among all players. Per Wikipedia:

Gipp was voted into the inaugural College Football Hall of Fame class on December 14, 1951, at 3:27 a.m., in memory of the time and date of his death.

George Gipp Memorial Park was dedicated on August 3, 1935, in his hometown. A plaque kept in the park lists former George Gipp Award-winners, given to outstanding senior, male athletes from Calumet High School.

In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS George Gipp was named in his honor.

He was ranked No. 22 on ESPN’s Top 25 Players In College Football History list.

HEAD THE FINAL HOURS

On Dec. 14, 1920, George Gipp died in St. Joseph’s Hospital in South Bend, less than a month after he played his last game for Notre Dame. During his illness, the Notre Dame students kept a prayer vigil going for Gipp. He was buried amidst a blinding snowstorm on the shores of Lake Superior in his hometown of Laurium, Michigan. The following poem by Quin A. Ryan recounted the drama of Gipp’s final hours:

The little town in Michigan

Is tucked between the snows.

A norther from Superior

Is calling as it blows

Full many a hundred yards or more

Lie down the village street

And seem to wait the darting pass Of famous cleated feet.

The mining shafts of Laurium

Are goal posts in the gloaming

And the treetops sound a whistle

To the copper miners homing

A murmur in the wind today

To all the native hearers

And whirling gusts from far Canuck

Are twenty thousand cheerers

The game is on! And through the snows

The norther’s sweep and dip

The wind is calling signals

To its brother halfback Gipp

The Indiana prairie lands

Are blanketed with snow

The Golden Dome of Notre Dame

Regilds the sundown’s glow

On the medieval campus In the early frosty flurry

Two thousand men are harking

To the wind’s uneasy scurry.

A rat-a-tat of flying feet

Is borne from Cartier

Tho’ the gridiron is barren

And the dark is in the air

Is it Army, Navy, Georgia?

Is it scores they now remember?

Or classic catches, leaps and runs

This evening in December?

The game is on! And o’er the field,

The word on every lip

The wind is calling signals To its brother halfback Gipp!

— Quin A. Ryan