Nov. 10, 2011

By Lou Somogyi, Blue & Gold Illustrated

Engraved deep into the stone on the side door of the Basilica of Sacred Heart at Notre Dame are not merely words but a way of life: “God, Country, Notre Dame.” It weaves together the school’s spiritual and patriotic elements while enjoining its loyal sons and daughters who are, as the Victory March states, “strong of heart and true to Her name.”

With the trip to Washington D.C. this weekend to face Maryland for the second time ever in football, Notre Dame’s theme of “Country” — especially in the United States military — is prominent in the nation’s capital.

From a football perspective, Notre Dame’s military history might seem confined to its rivalries with Army, Navy and Air Force. Nine times from 1969 through 2006, the Irish played the three services branches in the same season, and in seven of them — 1969, 1973, 1974, 1977, 1980, 1995 and 2006 — Notre Dame unofficially captured the Commander-In-Chief’s Trophy by sweeping the triumvirate.

It was in 1913 that the fledgling Notre Dame football program made its first major splash in the East Coast with a 35-13 victory versus Army, whose players included Dwight D. Eisenhower, the World War II commanding general who would serve as the United States President from 1953-61.

It was through the rivalry with Army in the 1920s that Notre Dame head coach Knute Rockne helped establish the Fighting Irish as “America’s Team” in the media capital of the world, New York City.

By 1927, the United States Naval Academy was added to the Notre Dame slate — and it has continued uninterrupted since then. The Air Force Academy didn’t begin its football program until 1955, but by 1964 it too became a regular on the Irish schedule, with the two schools meeting for the 29th time just last month.

What is the genesis for such a strong affinity between the military and Notre Dame?

“Ever since 1858 when the student-organized Continental Cadets began marching across campus in their blue and buff American Revolutionary-style uniforms, Notre Dame has been teaching students how to be good soldiers,” wrote John Monczunski in the Spring 2001 Notre Dame Magazine.

“Fair Catch” Corby

While most Notre Dame enthusiasts are aware of the “Touchdown Jesus” mural on the Hesburgh Memorial Library that overlooks Notre Dame Stadium, plus the mammoth “We’re No. 1 Moses” statue on the west side of the library, the history behind the “Fair Catch” Corby statue is not as well known.

Father William Corby was a 30-year-old priest who served as the chaplain of the famous Irish brigade that fought Civil War (1861-65) battles from the First Bull Run to Appomattox.

It was during the bloody three-day battle in Gettysburg, Pa., where more than 46,000 troops from the Union and Confederacy were killed, wounded, captured or ended up missing from July 1-3 1863, that Corby led his men in prayer and pronounced general absolution.

A picture of the dramatic event, with the battle raging in the background, was taken with Corby delivering the absolution with his right hand raised — similar to a fair catch in football. In 1910, 47 years later, sculptor Samuel Murray shaped a bronze statue of Corby that was placed at the exact spot in Gettysburg where Corby delivered the absolution. A duplicate now stands outside Corby Hall, next to Sacred Hall, on the Notre Dame campus.

After the war, Corby served as Notre Dame’s president from 1866-72 and 1877-1881, prior to his 1897 death.

In addition to Corby, Notre Dame had a role in many other facets of the Civil War:

Seven other Notre Dame priests joined Corby as chaplains in the War Between the States. Two of them died from yellow fever in the South, and a third, weakened by the war, passed away a few years later.

Eighty-nine Holy Cross sisters left Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s College to serve as nurses during the Civil War.

Two generals for the Northern Army came from Notre Dame — Williams F. Lynch and Robert W. Healy. It was in 1859 that Notre Dame president, Father Ed Sorin, appointed Lynch to head up the Continental Cadets. Healy would work with General William T. Sherman.

It was Sherman’s march through Georgia that rivaled Gettysburg as the most devastating campaign of the war. What is not as well known is that while Sherman was marching through the South, his wife and children were living at Notre Dame. Two of his boys were also enrolled at the minim department of the University. A third son, a baby, died during the course of the war and was buried in Notre Dame’s community cemetery, according to Don Heltzel in the Feb. 28, 1941 Notre Dame Scholastic.

The Legend Of Shilly

As president of Notre Dame, Corby instituted military training at the school in 1880, and two years later the program offered academic credit.

The Spanish-American War in 1898 also had a Notre Dame tie. In 1897, Notre Dame student John Shillington participated in a baseball game for his school in his hometown of Chicago, and he remained there while the team returned home. This led to his expulsion, and in his sorrow he joined the Navy.

He was assigned to the Battleship Maine. There, according to Arthur J. Hope C.S.C., author of “Notre Dame — One Hundred Years, ” the popular former student wrote to a Notre Dame friend: “I often think of Notre Dame, I can picture her daily, and in my reminisces of her, a tear is often brushed away. . . . I suppose `Shilly’ is forgotten by people at the old college, and I don’t blame them. Though forgotten, I shall always hold Notre Dame near and dear to me.”

Not long thereafter, Feb. 15, 1898, the Maine, sent to Havana, Cuba to protect U.S. interests in a Cuban revolt against Spain, exploded. It killed Shillington, and precipitated the Spanish-American War.

Notre Dame took a personal stake in the tragedy, and a campus monument is dedicated in his memory.

By the onset of World War (1914-18), Corby’s military training implementation had become a requirement for most Notre Dame students, and in 1917 its application for the government’s Student Army Training Corps (SATC), the precursor to today’s Reserve Army Training Corps (ROTC), was accepted.

The United States didn’t partake in World War I until 1917. Approximately 2,200 Notre Dame students entered the uniformed service, and 46 were killed in action. Their names are the ones memorialized at the “God, Country, Notre Dame” entrance.

Navy Saves Irish From Sinking

While World War II raged in Europe during the early 1940s, it was becoming evident that the United States isolationist policy from entering the war would be in jeopardy.

In need of better cash flow as a private school, Notre Dame president Rev. Hugh O’Donnell offered the school’s facilities to the armed forces as a training ground. During World War I (1914-18), the Army operated a Students Army Training Corps (SATC) program on the Notre Dame campus. This combined military training for students who also were majoring in their college courses.

However, in the early 1940s, the Army did not respond to O’Donnell’s invitation — but the Navy did. In Sept. 1941, it established the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) where approximately 150 Notre Dame students per year enrolled.

In early 1942, Notre Dame turned over four of its resident halls on the South Quad to the Navy for its V-7 program, which also was known as the Midshipmen’s School.

During that transformation, the Navy constructed a drill hall and a headquarters/classroom building on the north side of the campus — where today’s Hesburgh Memorial Library is located.

With the United States fully engaged in World War II by 1943, the Navy needed more men to serve and it again teamed with Notre Dame to form the V-12 program. An estimated 12,000 officers completed their training at Notre Dame between 1942 and 1946.

“We were out of business during World War II,” noted 1952-87 Notre Dame president Rev. Theodore Hesburgh in a 1992 interview with the South Bend Tribune. “Navy came in and kept us afloat until the war was over.”

Hesburgh vowed that under his watch the football series between the two schools would be kept as long as Navy wanted it continued.

To this day, Navy has never wanted to back out.

The 1943 Irish national title football team included 14 Navy apprentice seamen, most notably sophomore quarterback John Lujack, who would win the 1947 Heisman Trophy, 12 transfers who were part of the Marine branch of the V-12, and 17 Marine privates, among them future College Football Hall of Fame inductees Ziggy Czarobski at right tackle, All-American right end John Yonakor, starting left guard Pat Filley and1943 Heisman Trophy winner Angelo Bertelli at quarterback.

Several members of Irish teams won Purple Hearts: George Dickson (1949), who fought in Normandy on D-Day, Bob McBride (1941-52, 1946), a top assistant for head coach Frank Leahy after the war, Gus Cifelli (1946-49), and Luke Higgins (1942). Awarded the Bronze Star for his reconnaissance work while swimming through underwater mine fields in the Pacific Ocean was future College Football Hall of Fame inductee “Jungle Jim” Martin, who never lost a game while he starred at Notre Dame from 1946-49.

Tragically, former Irish players who made the ultimate sacrifice in World War II included Jack Chevigny (1926-28), George Murphy (1940-42), Hercules Bereolos (1939-41), Harold Borer (1938), Frank Cusack (1942), Tom Creevy (1942) and Jack McGinnis (1942).

Chevigny was the halfback who scored a touchdown in the famous “Win One For the Gipper” upset of Army in 1928, and served as an assistant for Rockne’s 1929 and 1930 national champs.

The former head coach of Texas enlisted in the Army in 1943 at the advanced age of 37 and died in battle two years later in Iwo Jima, where the Marine Corps suffered 5,391 deaths during five weeks of fighting.

According to Monczunski in his Spring 2001 Notre Dame Magazine article, ROTC’s peak at Notre Dame came in the late 1960s when some 1,600 Notre Dame students were in uniform. However, the Vietnam War heightened an anti-military sentiment, and by 1974 the ROTC figure on campus had dropped to 442.

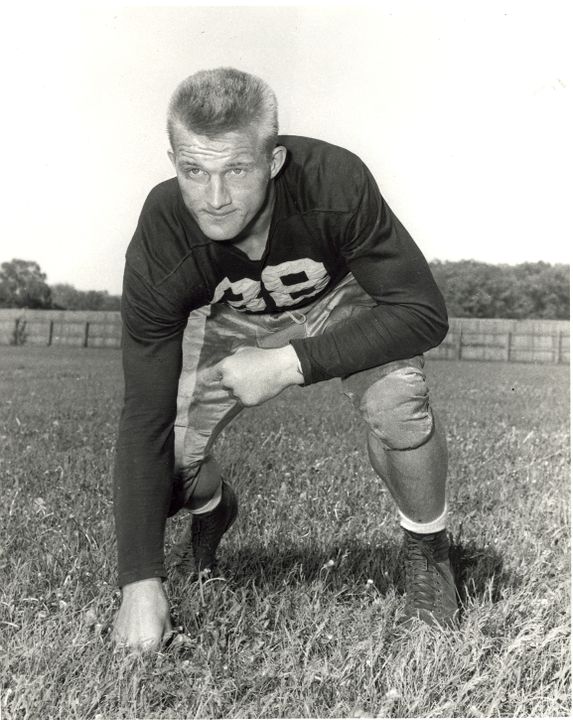

Still, there was one more Notre Dame legend established during these tumultuous times, this by 1967 Irish football captain Rocky Bleier, who started for the 1966 national champs but was only a 16th-round draft pick by the NFL. A handful of NFL players received draft notices for the Vietnam War, and Bleier was one of them during 1968 training camp.

“Having lived in Wisconsin, I knew that every Packer was in the Reserve or the National Guard, so my assumption was if you make a professional team, they get you into the National Guard,” Bleier said. “Bill Austin was the Steelers’ head coach and he took me aside about a letter that came. It was my 1-A classification up in Wisconsin.

“He told me, `We think you’re good enough to make the team and we’ll take care of this for you’ – whatever that I meant. I didn’t care. All I cared about was the comment `you’re good enough to make the team.’ “

Ultimately, everything fell through the cracks for Bleier, who was drafted into the U.S. Army in December of 1968 and shipped to Vietnam in 1969, serving with the 196th Light Infantry Brigade.

“What were my choices?” he reflected. “One was doing my service because I was drafted. I couldn’t go into the reserves. Second was I could go to jail, or third, I could go to Canada. Also, I could enlist and go to officers’ candidate school, but that would have extended my time.

“What I wanted to do was put my time in and get back out and pick up my life, whatever that may be thereafter.”

On August 20, 1969, Bleier was wounded in the left thigh when his platoon was ambushed in a rice paddy field. Then, an enemy grenade landed nearby, spreading shrapnel into his right leg.

“I remember scrambling to cover and trying mentally to make a pact with God,” he would recall years later. “I didn’t want to make a rash promise like becoming a priest or recluse of any kind. I just prayed and said if I got out of this and back home, I’d live a life that tries to help people.”

A recipient of the Purple Heart and Bronze Star, Bleier was rated 40 percent disabled when he was discharged. During his stay in a Tokyo hospital, he was informed that he would always walk with a limp. He weighed just 165 pounds when he arrived back in the United States, where he was introduced at halftime by Notre Dame president Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh in the 1969 home game with USC. On the same field where two years earlier he ran with aplomb, Bleier now required a cane.

“My focus was still on wanting to play football,” Bleier said. “I had family support and one of the things I most cherished while I was in the hospital overseas was I got a postcard from (Steelers owner) Art Rooney saying, `We’re still behind you. Team’s not doing well, we need you.’ He took that time…all those little things became positives.”

He became a starter for four Super Bowl champions while at Pittsburgh, and one of the most respected motivational speakers in the country.

Since the end of the Vietnam War, the ROTC has thrived at Notre Dame, and each unit has been recognized among the best in the nation by its respective uniformed service.

The Army, Navy, Marine and Air Force ROTC Units eventually established the US Notre Dame Command. USNDCOM is the first unified command in ROTC in the nation.

God, Country, Notre Dame, indeed.