Sept. 16, 2016

By Jim Lynch

Jim Lynch was captain of the 1966 University of Notre Dame football squad that finished as the consensus national champion. A linebacker from Lima, Ohio, Lynch as a senior in ’66 earned consensus first-team All-America honors and led the team in tackles with 106. He won the Maxwell Award as the top player in the country, earned Academic All-America honors and also was awarded a postgraduate scholarship by the National Football Foundation. Lynch went on to star for 11 seasons with the Kansas City Chiefs. In 1992 he was selected to the NFF’s College Football Hall of Fame. Lynch and around 70 other members of the 1966 squad have returned to campus this weekend to celebrate the 50th anniversary of their national title. This is his story of Notre Dame’s 1966 national championship season.

There was plenty for us to be focused on coming into 1966. We had raised the expectations even though the 1965 season (7-2-1 record) was not the kind of year we were looking for. We had some glaring weaknesses and we were trying to address those. I do think going into that next year (1966) we really had to have a sophomore class that was going to produce. The junior class was producing and the senior class was producing. But we really needed to have at the skilled positions somebody like a Terry Hanratty and somebody like a Jim Seymour. And, low and behold, that’s what happened.

There was an unbounding faith in Ara Parseghian. It was really a luxury to play for a coach where you felt like you were never going to be out-coached. You knew you were going to be put in a position where you were going to have an opportunity to win the football game-and not be in a game where you were going to be out of it from the start or having to spend the whole fourth quarter trying to catch up. That was not in our DNA.

Everybody went into that season with an open mind-I don’t think there was any overconfidence by any stretch of the imagination going into our senior year. Our goal was to win every game. I never worried about whether or not we would be ranked number one or be national champions, and I don’t think anyone else worried about that either. We wound up being national champion and ranked number one, but the focus was on trying to win every football game and then see where everything falls.

The opener against Purdue maybe looked like an even game coming in. We played four teams that season that were ranked in the top 10 when we played them and that was the first one. They had a guy by the name of Bob Griese at quarterback who the year before had completed 19 of 22 passes (for 283 yards and three touchdowns) against us when they beat us (25-21) at Purdue. He was back, so from a defensive standpoint, as far as we were concerned, we were playing a powerhouse. And, of course, the first touchdown they got in 1966 was when Leroy Keyes ran back a fumble (94 yards), but then we came right back and scored (on a 97-yard kickoff return by Nick Eddy). It was a tough opening game. It was a game where we thought we were pretty doggone good, but nothing proves out like a live football game in front of your home crowd. We ended up winning that game fairly handily (26-14). So we were off and running.

It was a great start for Hanratty (16 of 24 for 304 yards) and Seymour (13 catches for 276 yards, still the single-game record for reception yards). Plus, they were such great guys. It was a team that had great character and had a lot of characters. It was a group of guys that tended to their knitting–they got down to playing the game of football the way it was supposed to be played. It was a lightning-in-a-bottle situation that we were caught up in. You keep trying to get that feeling all over again, but it just comes once in a while.

The very first game under Ara in my sophomore year we went to Wisconsin to play. Milt Bruhn was their coach and he was a big, big name at that time. But Ara kept telling us in that 1964 season, “If you guys do what we tell you to do, you’ll win.” And we went to Wisconsin and we won the doggone football game because we did what he told us to do. You build from that. You can’t talk about the 1966 season without talking about the ’64 and ’65 seasons even with some of the great moments and even some of the mediocrity of the 1965 season. It (1966) was the third year under Ara Parseghian, the third year of the program on defense with coach John Ray, and he was like a stern father to everybody that played defense for him. So there was a lot going for us. It was a matter of sorting things out and finding out if we really did have the talent that we thought we did. Certainly the game against Purdue and the next few were very important.

I think the turning point–when we had believers all over the country–was when we won at Norman against Oklahoma. That was the fifth game and they were ranked in the top 10. Not only did we beat ’em but we beat ’em soundly (40-0). From that point forward there was a growing confidence in the abilities we had.

I think we were ranked number one for the first time the week we played at Oklahoma, but I don’t remember it having much impact or creating more pressure. Everybody took a page out of Ara Parseghian’s book, and Ara put more pressure on himself than anybody else could. We put a lot of pressure on ourselves to perform well. It didn’t make any difference who your opponent was, what your ranking was or what their ranking was. You had an obligation to play up to your potential. That was driven into the heads of everybody on that ’66 team. There was an expectation as you looked across the locker room that this guy’s going to play as hard as he can, so you don’t want to let him down or yourself down or the team down. That was the attitude. It’s kind of hard to describe, but the outside pressures were not nearly as severe as the pressure that came from within our team.

Our defensive statistics that season were phenomenal. I don’t know that some of those numbers will ever be matched at Notre Dame. It was a different game-people say, “I wonder what your team would do now?” Well, I don’t really know how we’d do now – but given the time and the people involved and the work ethic on campus, there were a lot of things we had going for us. You had a very homogeneous mix to coach, you had some of the best talent and the best minds in the game of football, you had a defense that was put together that had all kinds of combinations and complications for an offense to block. You had a guy in John Ray who was adamant about, “This is our turf” and you had guys that really bought into that. Not only did you have guys that bought into that, you had guys like Kevin Hardy and Alan Page and Pete Duranko and Nick Eddy and up and down the line. I remember when Ara came in, he’d get a team that had two running backs that were as big as doors and he moved them to offensive and defensive tackle. One of those guys was Pete Duranko. So an awful lot of credit has to go to the coaching staff for what they did.

I think I counted out of the 22 people who started against Michigan State, nineteen went into the pros off that list. There were guys like Don Gmitter who became an architect and John Horney who became a physician. But there were a lot of guys who not only got drafted but they spent a lot more than just a few months in the NFL.

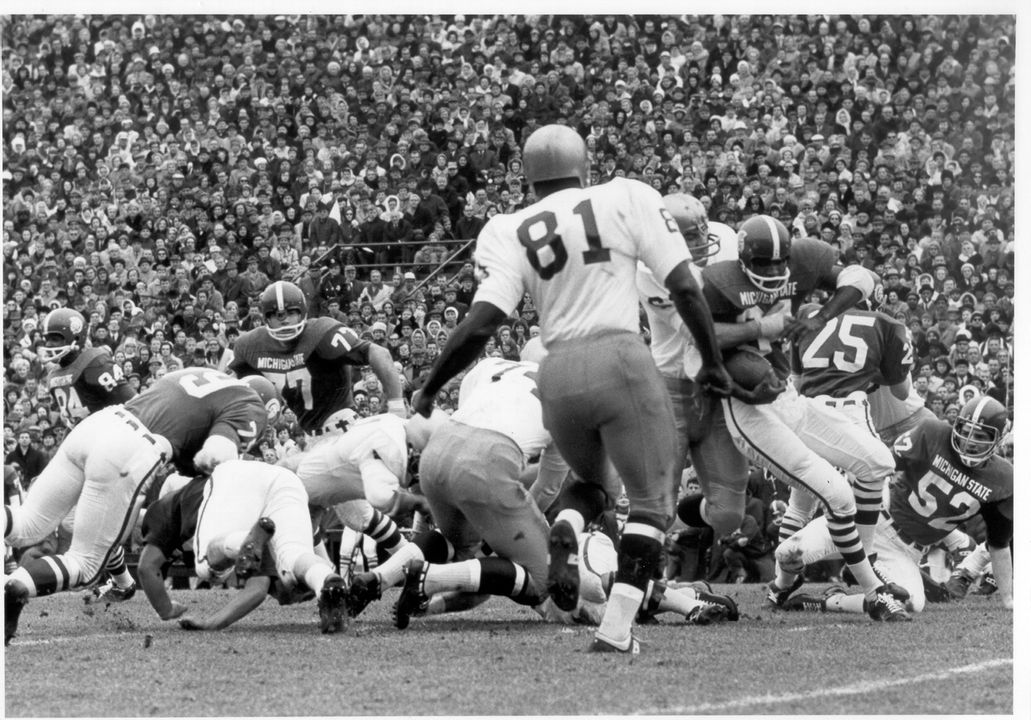

I was glad that we finally got to the Michigan State week. We kept on winning and Michigan State kept on winning–and people kept on talking about the showdown that was going to be happening in November. We would wind up having 40 or 50 reporters at our practices that week. We weren’t used to having 40 or 50 people at a practice ever. They’re not only watching practice, they all had a pencil and a pad in their hands. After practice you would have a press conference without much to say-most everything had already been said. We held up our end and Michigan State sure as heck held up their end and we knew they would. We knew it was going to be a very, very tough football game that we were going to have to play.

The hoopla around it was something to behold. It could have been very, very distracting. But Ara was a coach where, if you were playing an XYZ team that had won one game all year long and you were playing them the sixth game, he wasn’t going to say, “Boy, these guys are really hungry and they can really beat you.” He wouldn’t say that. He did not kid around or try to fool you into doing something. He would say, “You guys are a lot better than this team. You’ve got to go out and play the way you can and you can beat that team by 25 or 30 points.” He didn’t try to get you emotionally charged up about everything. He said, “You’ve got a job to do and you go out and do it.”

We knew going to play Michigan State that they were loaded with talent. I think it was the best team Michigan State has ever had. They certainly were as good a football team as we played in the years I was in college.

It was a physical game. Maybe the hardest-hitting game I’ve ever been in was the game against Michigan State the year before in 1965 (Michigan State won 12-3 at Notre Dame Stadium). We were held to negative yardage rushing. That was a behind-the-schoolhouse fistfight, and I don’t care who you are, nobody looks forward to a fistfight. But the ’66 game absolutely lived up to that same billing. That Michigan State game in 1966 was a lot bigger than when I played in the Super Bowl in January of 1970.

It was a surprise to everybody on the Notre Dame team that it ended in a tie. Nobody involved in the countdown to the game ever even considered it might end in a tie. So, from that standpoint it was an absolute surprise. Were you successful or not successful in that game? One thing we were successful in was that we were down 10-0 and we didn’t get beat. It was a see-saw game right from the start. But we were not a happy football team leaving East Lansing, that’s for sure.

I can’t speak for everybody else, but for me, I just remember being so physically and emotionally drained that next week. But we had another challenge against another top 10 team on the road at USC. There were some bitter memories of playing against them when we got beat in 1964 after we were 9-0 going into the last game of the season. They knew what they were doing-John McKay was their coach and they had great players. We go out there and win a game 51-0. If anybody would have told you that, you would have looked at them like they were crazy. There was no way you should beat that team 51 to nothing. It was just one of those unbelievable quirks of nature, I think. Nothing that Southern Cal tried to do worked, and everything that Notre Dame tried to do did work. I’ve got to believe that our team was pretty emotionally spent going out there that week, so it was hard to explain. Given the score, I was on the sidelines most of the second half. I was dumbfounded myself.

I’m sure people were talking about the national championship after the game, and yet it’s pretty much out of your hands. As a player all you do is what you can do. Our goal wasn’t to win the national championship, at least mine wasn’t. Our goal was to win every game that we played. If we win every game that we played then we should win the national championship. But we did not get beat in any of the 10 games we played that year. We didn’t win all 10, but we certainly didn’t get beat. So there was a reasonable chance after the 51-0 win, which again was unbelievable, that we would win it. But it’s in somebody else’s hands, so you didn’t worry about it or at least I didn’t worry about it.

In those days the national championship was voted on and determined before any bowl games. There weren’t that many bowl games back then-it was a different world, different time, different everything. You had two teams that were undefeated and had tied once and then Alabama was undefeated and untied and they wound up number three. It was just the vote. We had a banquet in early December like we always did, but I don’t really remember that much about it.

As time goes on it becomes a bigger deal. When we won that year, a national championship ring was not automatic by any stretch. A lot of the players had it in their own minds that, “Well, we’ve got a class ring, we don’t need another ring.” We celebrated, but it wasn’t like we were going for a Super Bowl ring like they do now. We have a national championship ring now that you can buy, but it came after the fact. That just wasn’t the way you did it back then.

Ara generally was serious in his approach, but we had guys on that team that kept things loose-George Goeddeke, Pete Duranko, Alan Page. You had guys on that team that were a little different than some average guy you’d just drag in off the street. They were pretty dedicated, pretty bright people. They’d come up with these crazy little poems each week, and there would be this good-natured rivalry between the offense and the defense. We’d make fun of each other. The practices had the defense on one side of the field and the offense on the other side. If you had an hour and a half practice, you’d have a mix of the two for at most a half-hour.

What sticks with you is that you can’t evaluate that year without looking at some of the seasons that built up to that year. You can’t evaluate an Ara Parseghian or a John Ray or Tom Pagna without looking at their body of work. And what kind of people they were. It always resounds that we’ve got a University that attracts great people. I appreciate Ara a lot more today than I did when I was 21 years old. We’ve all benefitted from gaining some comparative skills in that regard.

Edited by John Heisler, senior associate athletics director at the University of Notre Dame.