Thom Gatewood: the Power of Vision

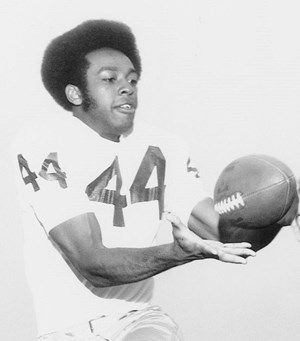

By Thom Gatewood '72Thom Gatewood graduated from the University of Notre Dame in 1974 as the first Black captain of the Notre Dame Football program. The Baltimore native set almost every receiving record in program history during his All-American career. A member of the College Football Hall of Fame, Gatewood spent two seasons in the NFL after being selected by the New York Giants in the fifth round of the 1972 draft. He went on to serve as director and stage manager for ABC News and ABC Sports, receiving both an Emmy and Peabody Award for his work. Gatewood currently runs his own advertising specialty company, Blue Star Products.

This installment of Signed, the Irish is part of a yearlong celebration in honor of Thompson’s legacy and the extraordinary contributions by our Black student-athletes.

After 50 years of reflection, I could talk for the next six weeks.

Prior to my sophomore year at Baltimore City College High School in the 60s, I never played organized football. Never had a football coach, never saw a playbook, never engaged in formal strategy sessions.

I was a baseball kid from the time I could put a glove on with dreams about the majors.

During that same period, Notre Dame Football was winning a national championship in 1966 with one African American man spotlighted on that team of stars, Alan Page.

But I never heard of Alan Page. I never watched Notre Dame win that national championship. I never learned about the integration that was unfolding at Notre Dame and other Conferences like the Big Ten. I missed it, because football wasn’t my love.

My junior year, I began playing football, entirely because my friend group did and I didn’t want to be left out… not that my parents had any idea. As far as they were concerned, I was at study hall and hanging out with my mates and playing baseball… not playing organized football!

My dad was a construction guy, a blue-collar guy who worked six days a week. My parents weren’t sports people and we didn’t get a newspaper, so there was no sports page to read or to see my name listed there.

At every level of my education, I was at the top of my class, an honor student. My goal was to be the first kid in my immediate family to get a college degree; the only person in my family to have a degree was my uncle, Clifton Gatewood. His work was unparalleled; he was a minister in New York who walked in marches alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who participated in freedom rides, who helped orchestrate so much throughout the Civil Rights movement.

In February of my senior year, I was ready to commit somewhere else to play football. But George Young, my mentor, history teacher, and football coach, said to me, “Do me a favor. Don’t commit to a school for the next two weeks.”

Now, George Young recognized athletic talent and, more importantly, cared for his students and wanted to ensure I had the best academic future, too. He would go on to work in the NFL for the Baltimore Colts under Don Shula and then followed Shula to the Dolphins (two Super Bowl wins), and then managed the selection of players as GM of the New York Giants (another two Super Bowl wins).

So out of respect for this great man in my life, I waited.

That wait was him compiling a reel to reel film of me playing football to try and get the interest of Notre Dame.

The country was in turmoil and transition and, honestly, I didn’t even know where Notre Dame was.

But George Young encouraged me to visit.

“There’s two people at this school — Ara Parseghian and Theodore Hesburgh. If those two people are influencing your life, they can make a big difference.”

Ara Parseghian had won a national title and could provide an unparalleled national exposure.

Fr. Hesburgh had earned a Medal of Freedom for his leadership work on the Civil Rights Commission.

George Young. Ara Parseghian. Fr. Theodore Hesburgh.

These three guys are crossing paths in my life at the same time.

There was nothing to wow about in Coach Parseghian’s Rockne Building office. It was a cramped, small, little place with no window and this was a man who had just come off a national championship.

He was puzzling to me — this unbelievable man in an unassuming physical setting.

“I know you’re a good football player,” he told me, “but you’ve gotta be willing to put in time here. We can raise your talent bar a lot higher, but we don’t know you yet, we don’t know your character. I can’t make you any promises about being an All-American, but when you’re done at Notre Dame, if you put in the work, you’ll come away with the ability to support your family, your name can be in every household in America, you’ll have an experience unlike anything else, including a more level road to opportunity.

Five Black men accepted Coach Parseghian’s challenge in 1968.

Bob Minnix. Clarence Ellis. Albert Pope. Herman Hooten. Me.

At the time, it was the most African-Americans recruited in one class for Notre Dame Football, and it became our own support system.

Frazier Thompson, the first Black student-athlete at Notre Dame, didn’t have that support system.

At the University overall, less than 1% of enrolled students were African-American — you could be walking across the quad and you might not see another Black face. You were always the minority in every class, in every situation.

But four of the five of us found a home in Keenan Hall and having no athletic-specific dorm at Notre Dame allowed us to learn socially from our white counterparts.

Because of the racial climate that was brewing and flames fired up across the country, we stepped up having great race relations and learned from one another.

Outside of campus — race riots, violent episodes, hoses, and German shepherds attacking peaceful groups — we saw what was happening, and it hurt us, but we were able to talk it out between the group of five.

The intersection of football and race relations didn’t spill over into athletics because our business was football.

We heard the vulgarities across the line of scrimmage, we heard it in the stands. That was part of the pain Fr. Hesburgh was asking me to absorb and to turn it into a positive message.

I don’t remember looking across from any table or any place on the field or in the locker room having any doubts about my teammates who were white.

They had my back; I had their back.

We could compete on the highest level that the country could display.

There’s a Black man on TV and he’s my neighbor, he’s my brother. That is so cool.

It was purposeful. It wasn’t just a game.

It was so much more. A chance to make an IMPACT.

During my time on campus, David Krasna was the first Black president of the student body. He garnered a majority vote-get to earn that milestone. He would stay in politics and become a superior court judge. What an amazing signal to send to the rest of the world.

Justice Alan Page also made a similar jump and served as kind of a piston to help level the playing field in American politics.

The world was changing.

One day, I was called to Fr. Hesburgh’s office, and the whole time I was thinking what the heck could I have done to have the University president summon me to his office!

He talked to me about his job on the Civil Rights Commission. He talked to me about the issues that faced our world, about his association with Dr. King, about change and the importance of leadership.

And then, he wanted to know what was in my heart.

“When I view TV or other sources of media,” I told him, “I don’t see faces like mine there. I’m hearing stories from a different face, the faces that are here at Notre Dame, and we need more African-American students, professors and mentors on campus to give us the faith and confidence that yes, things are changing and we’re not stuck in the same world.

“I want to be a leader with a vision to the future like Coach Parseghian, I want to see faces like yours tell me that it’s coming, Fr. Hesburgh.”

He recognized that I was about to break out here and that, if I’ve got the gusto and the talent, then I’ll be given a performance platform and a leadership role that I’m ready to accept.

He asked me if I was a baseball fan.

“How’d you know that?” I asked him.

“I didn’t know that,” Fr. Hesburgh replied. “Do you know the story of Jackie Robinson?”

“He’s my hero.”

Fr. Hesburgh talked about Robinson’s grit and intelligence and how those two tools together were his strength. He understood the power in corralling his anger, the power of the media, the power of his struggle.

If I could corral my own impatience, my own pain, and turn it into something positive…

When you have talent, it can inspire and, if undetected by yourself or others, that talent may go unused. But if you can work that talent, preparing for the future, the reward at the end is going to be a high degree of performance.

That performance is the job, not my skin color.

It’s work. You’ve gotta put in the work. There’s no such thing as a natural born leader. Leadership is something that comes out of doing your job, out of having a vision. You cling to that vision.

That’s what I learned that day from Fr. Hesburgh.

That’s what he was telling me.

Quell the anger and don’t be influenced by outsiders.

Be influenced by your heart.

Give your spirit great thought.

Talk about the greatest orientation to a university!

Now here comes the payoff pitch.

Five years before he passed, I met Fr. Hesburgh in his penthouse office in the library, and he invited me to smoke cigars.

Please, light me up!

I’m having a glass of bourbon and we’re toasting and I didn’t bother to ask him if he recalled that conversation in 1969 when he asked what was on my heart.

“I’m older,” he said, “but there’s nothing wrong with my faculties.”

He paused before continuing.

“You are a tremendous ambassador for the University of Notre Dame, all over the world.”

That conversation was so cool and one I’d never forget.

The football world never leaves me.

I was a student first, athlete second. My obligation to my family was to get that college degree.

When I look at my achievements and accomplishments, and I have plaques for academic All-American, I know that I was a true student-athlete — a tradition that I would be able to perpetuate.

My mother used to say that “if you can replace yourself with a person like yourself, the world doesn’t really lose you at death.”

My next goal was that my daughter would get her degree to strengthen the academic Black community.

The tradition has now continued with my grandson, A.J. Dillon, who played football at Boston College and now plays for the Green Bay Packers.

Be influenced by your heart. Give your spirit great thought. And never forget the power of your vision.