Jan. 15, 2015

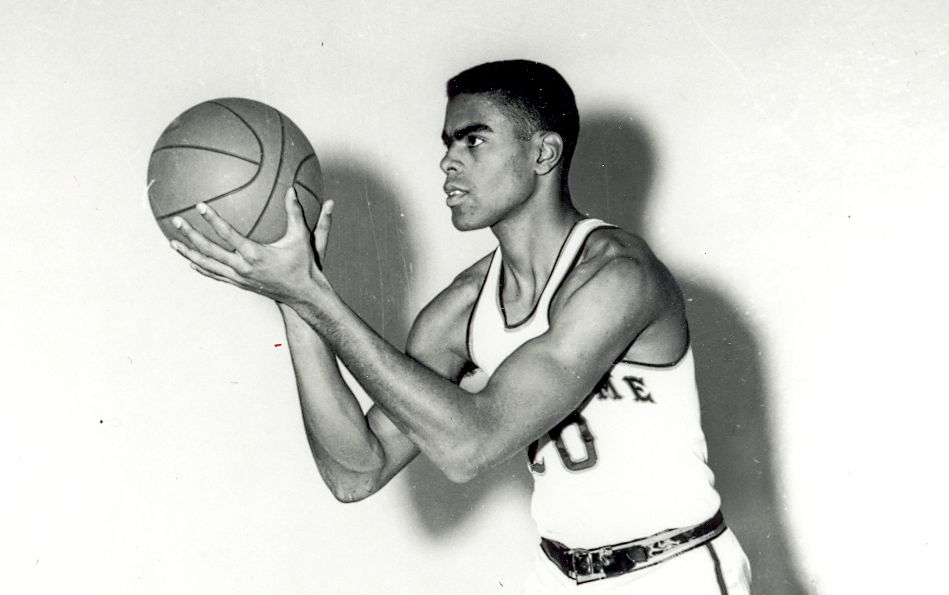

Nearly 56 years after he walked off a basketball court for the final time wearing University of Notre Dame blue and gold colors, Tom Hawkins is still fighting for rebounds.

“I averaged 23 points a game and 16.7 rebounds a game in my career at Notre Dame,” said Hawkins who graduated in 1959. “Round the rebounds up to the closest tenth, and give me 17 a game.”

Hawkins, whose 1,318 career rebounds serve as the longest standing record in the 109-year history of Fighting Irish basketball, will be inducted into the Notre Dame Basketball Ring of Honor Saturday. He will be the seventh person to join the pantheon of Irish greats that already includes Austin Carr, Adrian Dantley, Skylar Diggins, Luke Harangody, Ruth Riley and former men’s basketball coach Richard “Digger” Phelps.

A special ceremony is planned for Hawkins Saturday, when the No. 12 Irish take on Miami (2 p.m. EST tip-off at Purcell Pavilion).

Notre Dame’s first African-American student to earn All-America honors, Hawkins carved out a brilliant legacy long before the banner emblazoned with his name in blue and gold is hoisted to the rafters of Purcell Pavilion.

A graduate of Chicago’s Parker High School, the 6-foot-5-inch Hawkins became the first Irish player to average in double figures in scoring and rebounding in each of his three seasons (freshmen weren’t allowed to play under NCAA rules at the time). In his three varsity seasons at Notre Dame, he grabbed 1,318 career rebounds, a record that still stands. He is ninth on the Irish career points list with 1,820.

After graduating from Notre Dame, Hawkins became a first-round NBA draft pick and played for 10 seasons, mostly with the Lakers. He scored 6,672 points and hustled for 4,607 rebounds in his professional career.

Notre Dame men’s basketball coach Mike Brey said the decision to make Hawkins the next inductee into Notre Dame’s Ring of Honor was a slam dunk.

“I always ask some of our former guys, former coaches, about who should be inducted into the Ring of Honor, and it was the easiest decision of any of them to go up,” Brey said. “It was like, ‘Oh, yeah, Tommy has to go up this time.'”

According to Brey, Hawkins distinguished himself as a Notre Dame man far beyond the basketball court.

“Tommy was a trailblazer here,” Brey said. “He was a groundbreaker as an African-American student, but also as a basketball player. And then the manner in which he represented himself and the class act that he was, not only while he was here, but also later in life, he’s an unbelievable role model.

“After we made it public that he was going to be the guy, I had an outpouring from our former players, like, ‘That is awesome, coach. That’s the right guy.’ Almost every one of our African-American players said, ‘He was a role model for me. I will be back for this ceremony.'”

Hawkins was always proud of the righteous stand Notre Dame took during the turbulent social upheaval as the civil rights movement swept across America.

“This was a time of major racial conflict, and nationally segregation was the name of the game,” Hawkins said of playing in the late 1950s. “(Then Notre Dame president) Father (Theodore) Hesburgh at a press conference in 1955 told the world that anywhere Notre Dame’s minority students weren’t welcome, neither was Notre Dame. This was huge, because this was nine years before the first civil rights legislation, this was before Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott.”

Notre Dame wouldn’t schedule schools that didn’t allow African-American student-athletes on their campus. The Irish wouldn’t stay at segregated hotels or dine at segregated restaurants.

“Notre Dame was one of the first schools to take that kind of stand,” Hawkins said.

In 1958 the NCAA allowed Kentucky to play host to a men’s basketball regional on the contingency that the university had to find a hotel in Lexington that would allow African-Americans.

Notre Dame beat Indiana in the regional semifinal and took a 25-3 record into the regional championship game against host Kentucky.

“We lost miserably,” Hawkins recalled. “I’m not going to tell you we were jobbed, but I will tell you that I had three fouls in the first five minutes.”

Kentucky would go on to win the national championship, and Hawkins and the Irish were left to ponder what could have been.

“For me, the most important thing that happened there was right after we got into Lexington,” Hawkins explained. “The guys wanted to go to a movie. There was a theater just a few doors down from our hotel. We went there to go to the movie. The manager said, ‘Everyone’s welcome here. Whites on the main floor, blacks in the balcony.’ We said, ‘What?’

“Eddie Gleason was a guard on our team and a senior, and he said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding. We’re a team. We don’t segregate ourselves.’ He asked, ‘Where is there a theater that we can go and all enjoy a movie together?’ The manager said, ‘You’ll have to go to the black section of town.'”

Hawkins said Gleason called two cabs to meet the Irish at the theater. The team crammed into the two cabs and took off to see a movie – together.

“We got into those cabs and went to the black section of town and all of us went to the movie together,” Hawkins said. “That was Notre Dame.”

At Notre Dame Hawkins immersed himself in his education and the Catholic faith, even though he was a Methodist.

“The reason I didn’t get bitter was the education and the teachings Notre Dame gave me,” Hawkins said. “At Notre Dame there was this incredible blending and incredible shaping of what a Notre Dame man should be. They positioned me to become a man in a man’s world.”

Hawkins has been a Renaissance man since leaving Notre Dame. He played pro basketball, was a broadcaster for 18 years and served as an executive vice president in the Los Angeles Dodgers organization. He is an in-demand public speaker and a man of the arts. He recently published a book, “Life’s Reflections: Poetry for the People,” in which his poetry and narratives are paired with famous photographs and paintings that embody the message of the narrative.

“I feel I got the ultimate and a personalized education in my four years at Notre Dame, which has paved the way to success in everything else that I’ve done in life,” said Hawkins, who lives in the Los Angeles area.

“I’m very excited about coming back to Notre Dame for this honor. It’s hard for me to fathom that a record that I set some 55 years ago still stands. It tickles me. I had at least a 40-inch vertical leap, and I took all phases of the game seriously, not just scoring.”

Brey said Hawkins helped set the gold standard for Irish basketball players on the court and off.

“Tom Hawkins was the first of the rebounding machines,” Brey said of the two-time All-American. “It shows in his stats and where he is in our all-time rankings. I think he was one of the first guys, when he was in the NBA and then doing broadcasting, that became an ambassador for us. He used his high profile to really represent Notre Dame and Notre Dame basketball.

“Tom Hawkins put us in such a good light. This is a Notre Dame product. This is a Notre Dame men’s basketball program product. He’s such a class act. What a great ambassador he is, carrying the flag for Notre Dame and our program.”

Hawkins said he follows the Irish as much as he can. He watched Notre Dame’s game last week at North Carolina game on television and cheered on what was the program’s first victory on the Tar Heels’ home court.

“I have been intrinsically tied to Notre Dame,” Hawkins said. “I sent my son Kevin to Notre Dame on my ticket because I wanted him to experience what I experienced and get the same personalized education that I received.”

Kevin Hawkins played basketball for the Irish from 1978-81.

For Brey Saturday’s induction of Hawkins into the Irish Ring of Honor will be a special moment for all of Notre Dame and not just the basketball program.

“Tom Hawkins is so proud to be a Notre Dame man,” Brey said. “He’s so eloquent. I’m sorry I won’t be able to hear his speech live because I’ll be in the locker room. But I can’t wait to hear what he says because I’ll bet it will be eloquent and it will touch every point that needs to be touched.”

— by Curt Rallo, special correspondent