Oct. 11, 2012

By Craig Chval Sr.

If only Vince Boryla were truly color blind, he might have completed his entire college basketball career at Notre Dame, where he began it as a freshman in 1944. But we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves.

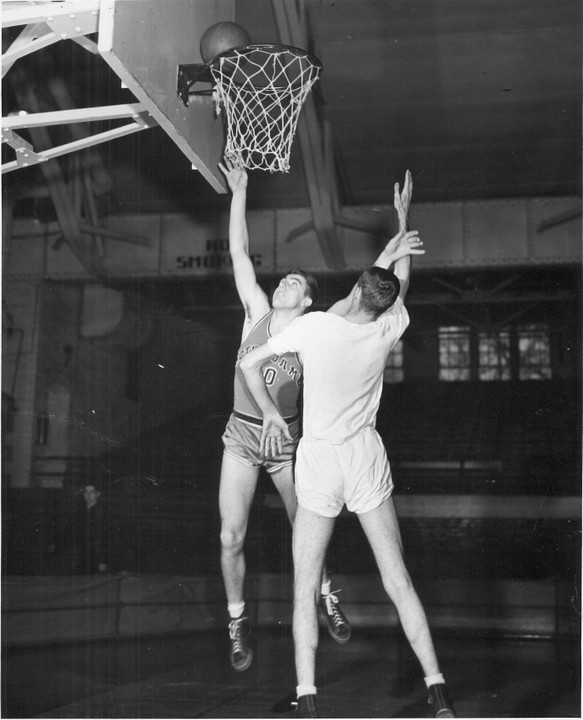

The East Chicago, Ind., native enjoyed a stellar freshman season for Notre Dame in 1944-45, captaining the squad as a freshman and leading the Irish with 16.1 points per game. Among those impressed with Boryla’s play as a rookie was an administrator with the Great Lakes Naval Training Base, whose team split a pair of games against Boryla and the Irish. Mindful that Boryla soon would be required to fulfill his wartime military obligation, he suggested that Boryla put in for a special services assignment with the Navy, which would have allowed him to play for the Great Lakes basketball team during his enlistment.

But the administrative chapters of Boryla’s military career contained enough twists and turns to fill a mystery novel.

By the end of Boryla’s freshman year at Notre Dame, he had received an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy. In connection with the appointment, Boryla took a preliminary physical examination while at Notre Dame, and that’s when he was informed that he didn’t pass the color perception test – that he was color blind.

With the Naval Academy seemingly out of the picture, Boryla reported to Great Lakes, planning to play basketball as part of the special services program, as once discussed. Soon after arriving at Great Lakes, however, he was summoned to see one of the base commanders.

“Emmett Williams,” Boryla says. “I’ll never forget that name. It’s amazing how I can remember that name from almost 70 years ago, and I can’t remember the name of the last guy I met.”

Williams told Boryla that he would be headed to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, after all. When Boryla asked about the color perception test, Williams had a ready reply.

“Oh son, son,” Boryla remembers Williams telling him. “Don’t even think about that. We’ll give you some books to study and you won’t have any problem with that.”

Williams gave Boryla two choices: accept the commission and attend the Naval Academy, or be deployed to Europe. Boryla received a 72-hour pass to discuss the “choice” with his parents, and then reported to Annapolis.

After completing “plebe summer,” Boryla’s career as a midshipman was in full swing when he was derailed by foot surgery. Following his recuperation, Boryla and his parents prevailed upon the Navy to let him return to Notre Dame, where he arrived just in time for the 1945-46 season, helping the Irish to a 17-4 record by averaging 15.3 points per game.

But there was still the matter of Boryla’s military commitment. So Boryla reported to the U.S. Army base at Fort Sheridan, Ill., where he spent nine or ten months before a transfer was arranged to Lowry Air Force Base in Colorado. There, Boryla played on the Denver Nuggets AAU team, earning a spot on the United States basketball team that competed in the 1948 Summer Olympic Games in London.

About the only thing that `48 U.S. team had in common with the 2012 U.S. squad that competed this summer in London was that both teams claimed gold medals in London.

While the 2012 team was accompanied by super-sized hype and expectations, the ’48 team – competing in the first Summer Games since 1936, due to World War II – arrived in war-torn London in virtual anonymity.

Boryla, who had the time of his life with his Olympic teammates, enjoying the six-day cruise to reach the United Kingdom as well as the team’s post-Olympic visit to Paris, noted one other similarity: thanks largely to the leadership of U.S. Olympic Team managing director Jerry Colangelo as well as head coach Mike Krzyzewski and his staff, Boryla saw an absence of selfishness and an unyielding commitment to the 2012 team.

After the Olympics and upon the conclusion of his military commitment, Boryla decided to transfer from Notre Dame to the University of Denver.

“Growing up in East Chicago, I thought snow was gray and grass was brown,” Boryla says with a chuckle. “Then I came out to Denver and saw the mountains and the white snow and green grass and I thought to myself, `This is where I’m going to make my life.'”

So much for being color blind.

Boryla led the Pioneers to an 18-15 record in 1948-48, averaging 18.9 points per game. Among those 15 losses was a three-point defeat at the hands of Notre Dame in the old Notre Dame Fieldhouse.

“It was really a crazy experience,” says Boryla. “I don’t think I missed a shot in warmups. I`ve never had a more fantastic warmup and never shot worse in a game.

“All those rosaries those priests were twiddling on the sidelines must have done something,” he says with a laugh. His rough night back in South Bend didn’t keep Boryla from being the only junior to earn a spot on the consensus All-America team for 1948-49. Since he had one year of eligibility left, he had unique leverage with the National Basketball Association’s New York Knicks. Aware that Boryla could have played one more year of college basketball and worried about losing the rights to sign him, the Knicks offered Boryla a rarity in those days – a three-year guaranteed contract.

Boryla made sure the Knicks got what they bargained for, averaging 11.2 points, 4.1 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game over his five years with the team, earning a spot in the 1950-51 NBA All-Star Game.

And then it was time to get back to Denver.

“It was a great decision,” says Boryla of choosing to settle down in Denver.

“When I came back in ’54, I had a wife, a car, a travel crib and two kids,” he says. “And I had $75,000 I had saved from running a summer camp in Denver for three or four years.

“I’ve always been very close with my money,” Boryla says. “I never looked at what I was making, but what I came home with. That was my simple Polish command.” To clarify, Boryla has always been very careful with his money, which is definitely not to be confused with being miserly. As one of the most successful real estate developers in Colorado for decades, Boryla is also one of Denver’s greatest philanthropists, although most of his contributions have been anonymous. Only in recent years has the 85-year-old Boryla been persuaded to allow disclosure of some of his generosity, and only because he became convinced that it might serve as an encouragement to others.

But Boryla wasn’t through with basketball after retiring from the Knicks; although it might be more accurate to say that basketball wasn’t through with him. Over the years, Boryla was recruited to serve as the Knicks’ head coach, and later as the team’s general manager. He led the Utah Stars to the American Basketball Association championship in his first year as general manager of that franchise, and was honored as NBA executive of the year in 1985, when he took over the Denver Nuggets. Boryla traded leading scorer Kiki Vandeweghe to Portland for three starters, improving the team’s win total by 14 games over the previous season, winning the Midwest Division and reaching the NBA Western Conference Finals.

Today, Boryla is retired, spending time with Mary Jo, his wife of 23 years (Boryla’s first wife died at age 62 as the result of Alzheimer’s Disease) and his five children, Karen, Mike (a two-year starter at quarterback for Stanford and former NFL quarterback), Mark, Matt and Vince, along with 15 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

Whether it’s playing basketball, coaching basketball, running a franchise, raising money for dozens of charitable causes or developing real estate – “buying ground,” as Boryla puts it – Vince Boryla has been a great success at everything he’s done.

“God gave me pretty good brains for a dumb Pollack,” says Boryla, the son of two Polish immigrants making light of an old stereotype.

Whether by way of God, his parents or elsewhere, Boryla also came by a great work ethic and most significantly, true compassion for others. As a basketball All-American, Olympic gold medalist, NBA all-star, NBA executive of the year and wealthy businessman, Boryla is best known today as a champion of charitable causes.

It’s a point not lost on his devoted bride, Mary Jo, who closes a conversation with six simple words: “Thanks for talking to my hero.”