Dec. 21, 2017

By Megan Golden

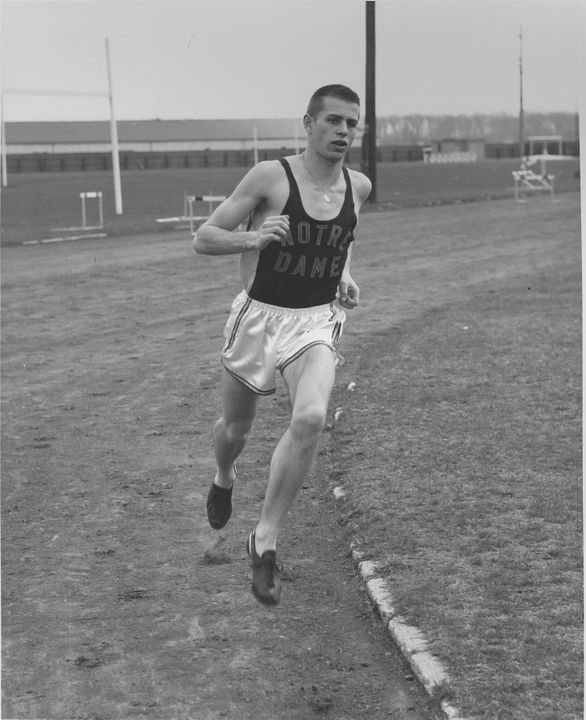

A three-sport high school athlete, Bill Squires was living in Boston, Massachusetts, in the 1950s when numerous collegiate track coaches began calling his home.

The influx of phone calls and athletic scholarship offers led Squires to hire a lawyer to field the various inquiries surrounding the middle-distance runner’s future. Squires, who lived with his mother while his father was away serving with the United States Marines, received more than 80 offers to compete with collegiate track programs across the country.

Squires spent time with his mother and his lawyer determining the best possible fit for himself. Reflecting on his personal goals and recognizing his urge to escape the New England region, Squires ultimately determined that Notre Dame was the perfect place for him to attend college.

“I happened to have a fond love of Notre Dame. I wanted to go into the priesthood,” he said.

Those aspirations quickly changed when Squires began his track career with the Irish. In high school, football and basketball were Squires’ priority, and he competed in track solely for the speed and endurance training that would make him quicker on the football field and the basketball court. During his time at Notre Dame, however, he realized this track thing might work out for him long term.

A two-time All-American in cross country, Squires recorded two top-15 finishes in the national championship four-mile race. Squires placed 14th (20:29) in 1954 and 12th (20:32.5) in 1955.

On the track, Squires was a top-three miler.

“They had me as the miler,” Squires said. “The event I enjoyed was the half mile. I was anchoring the mile relay and I had really, really good speed. I could run a good 100m, but from the 200m to the quarter mile, my speeds were really, really fast. I had my strength, and that was my thing.”

Strength. As an athlete, Squires learned the importance of strength versus speed. Three strength workouts each week, he said, will improve an athlete’s endurance.

His strength workout of choice? Four reps of 50 pushups.

“For myself, I was an all-around athlete because I was a basketball, football and track athlete. I would stay in shape all year,” he said. “I was really conscious of strength and speed. In a race, it’s who’s strongest at the end. That’s the difference.

“Coaches didn’t understand that speed and strength have to work together, hand-in-hand; the right dosage is the secret of success.”

Life After Notre Dame

Squires went on to compete internationally with the United States, an opportunity that allowed him to meet middle-distance athletes from all over the world and learn about different training styles and philosophies.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 brought several immigrants to the U.S. In addition, Squires said he met several Yugoslavian athletes around that time, who taught him about recovery time and the importance of rest.

“They didn’t race as much as we did in America; we raced every week,” he said. “In foreign countries, we raced every three weeks. There you don’t run, you race.”

Following his own athletic career, Squires served at the helm of the Boston State College track team, which won more than 40 championships from 1965-78. He also led the Greater Boston Track Club.

Years later, with several seasons of coaching under his belt, the 85-year-old still preaches the importance of strength in a distance runner’s training regimen.

“[As a coach,] I would change my programs. I was doing things that I saw were negative in my coaching, and I even had to tell a few of my own that they needed to blend speed and endurance together,” Squires said. “What’s endurance going to do? Endurance is strength. Speed is natural.”

One particular athlete stood out in Squires’ memory. A freshman once complained to Squires that he was struggling to break six minutes in the mile. After extending the athlete’s recovery time from week-to-week to three weeks between competition and also engaging him in strength training three days per week, the athlete moved up to the third-ranked miler in the nation by his junior year.

“I knew I had a talent for coaching,” Squires said. “God gives talents out, and mine was that I could take an average person and make them a champion.”

Hall of Fame Came Knocking

The USA Track and Field Hall of Fame sent a letter to Squires in October, notifying him of his approaching induction into the hall and inviting him to attend the 2017 induction ceremony.

Squires said his name is written in numerous small-scale halls of fame, but due to the international nature of the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame, this particular invitation was difficult to pass up.

With a little nudging from his son, Squires caved in and rented the $100 tuxedo and traveled to New York City for the ceremony on Nov. 2.

“My son said, ‘Don’t you want your grandchildren to know you were a very, very important person and you were very well-respected?'” Squires said. “I’m not a shy guy, but I’m not a pompous person. I always look the other way and let the other guy get the accolades. I knew how good I was athletically, and that was one of the traits the good Lord gave me.”

Squires brought home a diamond-studded ring from the induction and made it clear that he will not be seen wearing his newest jewelry.

“It weighs seven ounces,” he said. “It’s so heavy that my hand would fall off. A sumo wrestler would be able to wear it, not a person [like me].”

–ND–

Megan Golden, athletics communications assistant director at the University of Notre Dame, has been part of the Fighting Irish athletics communications team since August 2016. In her role, she coordinates all media efforts for the Notre Dame women’s soccer and cross country/track and field programs and is the secondary contact for women’s basketball. A native of Cleveland, Ohio, Golden is a 2014 graduate of Saint Mary’s College and former Irish women’s basketball manager. Prior to arriving at Notre Dame, she worked in public relations with the Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox.